PACE v1.0 Documentation

Table of contents

Introduction

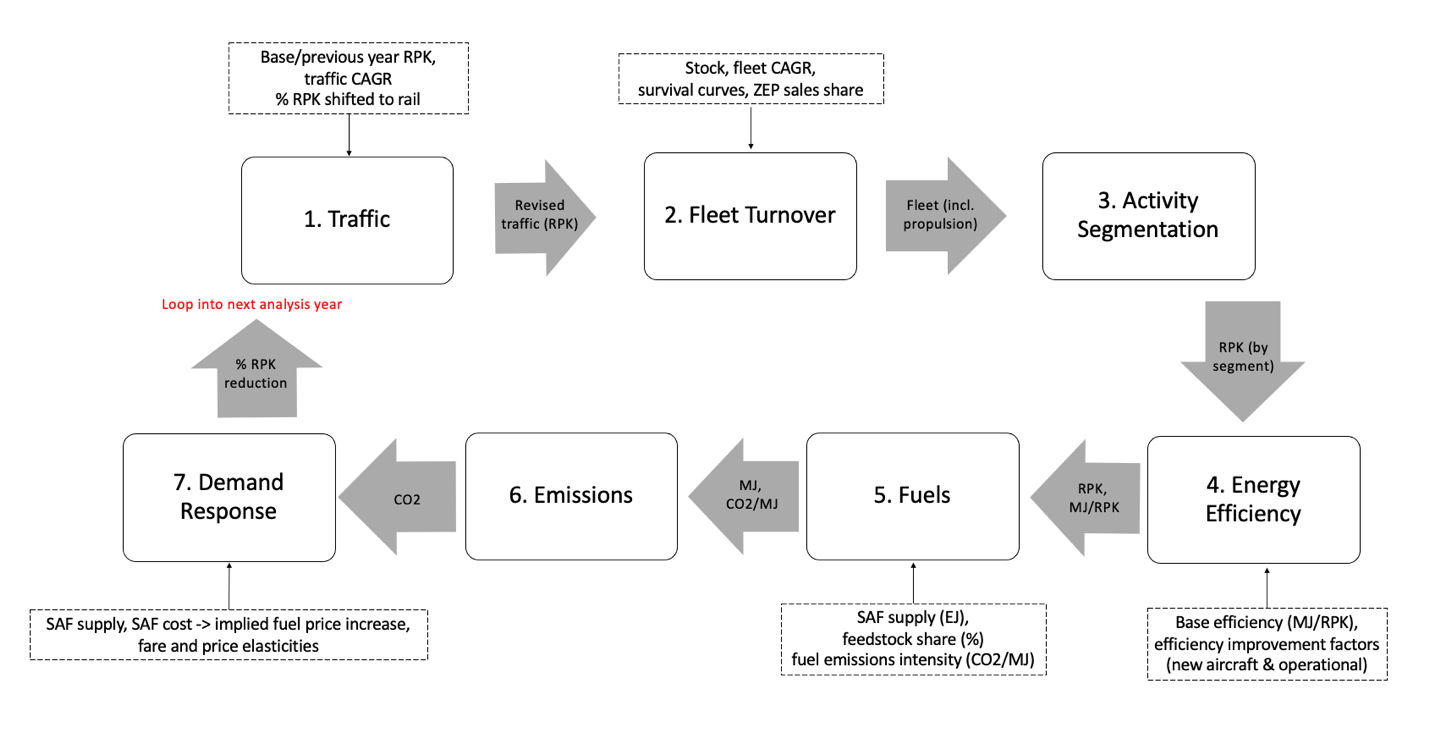

ICCT’s Projection of Aviation Carbon Emissions (PACE) model is a global aviation emissions model covering commercial passenger and cargo operations. The model estimates the well-to-wake carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in future years under different technology pathways. PACE can be used to provide policymakers with insights into actions needed to meet specific carbon budgets.

The model currently uses 2019 activity and CO2 data from ICCT’s Global Aviation Carbon Assessment (GACA) model as its baseline. The decarbonization levers include fuel efficiency improvement, use of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), introduction of zero-emission planes (hydrogen and electric), demand reduction in response to higher fuel prices, and modal shift to high-speed rail. The model iterates through each analysis year; the changes in traffic, energy, and emissions in one year will affect the modelled outcome of the next.

Figure 1. Model flow chart for each analysis year.

It is worth noting that the model treats SAF supply and cost as exogenous variables. The change in traffic growth or fuel efficiency does not affect the amount of SAFs in the system.

This documentation describes the inputs, calculations, and outputs of each module. There are two types of inputs: background inputs that enable model functionalities, and user-specific assumptions for various modeling scenarios. The 1.0 version of the model was used to model 2020-2050 emissions for ICCT’s “Vision 2050: Aligning aviation with the Paris Agreement” report. The “scenario inputs” section describes the specific inputs used for this project.

In addition, all input data are structured in the tidy data format. Every column is a variable. Every row is an observation. Preparing data in such a format is crucial to using the model.

Acknowledgments

PACE was first developed in 2022 by Xinyi Sola Zheng, Jayant Mukhopadhaya, Erik Pronk, and Dan Rutherford.

Modules

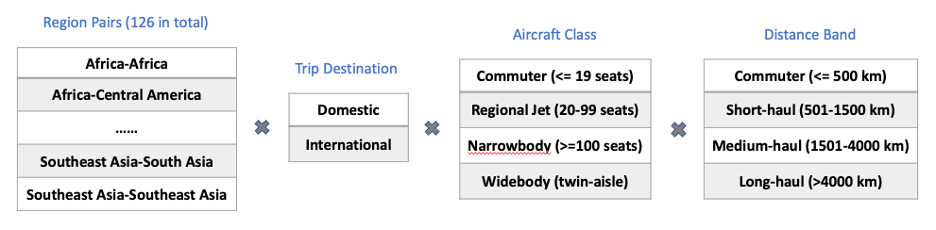

The PACE model performs analysis on the level of operational segment. Figure 1 shows how we define segments. We use the Boeing Commercial Market Outlook (CMO) and its 12 regions to divide traffic into region pairs. The CMO contains passenger traffic flow between 41 region pairs consolidates all other traffic into a “Rest of World” catchall. GACA data was used to extract the “Rest of World” traffic into omitted region pairs, deriving a total of 126 region pairs after excluding 18 region pairs where no passenger traffic was observed in 2019. We break down the operations within each region pair based on trip destination (domestic vs. international), aircraft type, and distance band, which results in 1,550 unique segments globally. These will be referred to simply as “segments” for the rest of this document. Note that only intra-region segments will have a domestic sub-segment, such as North America-North America, China-China, and so on.

Figure 2. PACE model operational segments.

The modeling processes of passenger operations will be explained first. Section 8 separately describes the methods used for freight, which is modelled at lower fidelity in the GACA model. In the actual model, the freight calculations are integrated into respective modules and do not have a stand-alone module.

1. Traffic

The Traffic Module handles traffic growth, demand response to ticket price increase, and modal shift to rail for relevant segments.

In the first analysis year, the model takes in base-year revenue passenger-kilometer (RPK) data broken down by segment, which come from ICCT’s Global Aviation Carbon Assessment (GACA) model. The model then matches the compound annual growth rates (CAGR) from Boeing’s traffic forecast to the base-year RPK data based on region pair. Table 1 shows the global average growth rates over the modelled time period. The Central Case rates are used by default.

Table 1. Traffic annual growth rates.

| Low | Central | High |

|---|---|---|

Passenger: +2.4% RPK p.a., 2019-2050 |

Passenger: +3.0% RPK p.a., 2019-2050 |

Passenger: +3.7% RPK p.a., 2019-2050 |

Freight: +2.6% FTK p.a., 2019-2050 |

Freight: +3.5% FTK p.a., 2019-2050 |

Freight: +4.2% FTK p.a., 2019-2050 |

In all the following analysis years, the model adjusts each segment’s CAGR based on the percentages of RPK reduction from ticket price increase in the previous year. These percentages of reduction are calculated in the Demand Module (see Section 7). For analysis years after 2030, when modal shift inputs are given, percentages of traffic shifted to rail are applied to relevant segments.

After adjusting CAGR based on demand reduction rates, the model applies the CAGR onto previous year (Y1)’s RPK by segment (S).

\[\text{RP}K_{S,y2} = RKP_{S,y1}*\left( 1 - PctRPKreduction_{S,y1} \right)*(1 + CAGR_{S,y1})\]The overall change in RPK is saved to inform the fleet growth calculation in the Turnover Module (see Section 2). The model also stores the adjusted RPK and CAGR of each segment for demand response calculations later.

2. Turnover

For each aircraft class analyzed, the Turnover Module calculates the fleet growth, ages all aircraft by one year, determines age 0 stock, and integrates ZEPs into age 0 stock based on expected sales shares.

Stock turnover

The overall fleet growth is assumed to be consistent with overall RPK growth. However, the growth of each aircraft class is differentiated. The model takes in annual fleet growth rates for each aircraft class based on industry forecasts. Every year, the model scales these growth rates up or down to match the overall fleet CAGR with the traffic CAGR.

The stock turnover function first takes in the fleet CAGR by aircraft class to calculate the total fleet size for each class. The function then adds one year of age to each row of the “stock by age” data and applies the survival rate matched from year-over-year survival curves. These curves are characterized by a Weibull distribution function, and they represent the fraction of vehicles surviving from one year to the next. ICCT developed these curves as part of an unpublished consultant report to Argonne National Laboratory in 2011. The fleet broken down by age is given for the base year. In this case, for each aircraft type (T), the vehicle stock in a calendar year (CY) of a given delivery year (DY) is calculated as:

\[\text{Stoc}k_{T,CY,DY} = Stock_{T,CY - 1,DY}*Survival_{T}*(CY - DY)\]Age 0 stock of each class equals the gap between projected total fleet size and total number of survived aircraft at age 1+. The age 0 stock (i.e., new sales) is then broken down by propulsion, based on the sales share of hydrogen and electric aircraft in that year, which are user inputs.

\[\text{Stoc}k_{T,\text{CY},\text{DY}} = ProjectedFleetSize_{T,\text{CY}} - \sum_{}^{}{\text{Stoc}k_{T,CY}}\]Zero emission planes (ZEPs)

The model allows for specification of multiple zero-emission aircraft with varying payload and range capability. The introduction year and sales share of these aircraft is input into the model as well. The stock of zero-emission aircraft is limited by the maximum percentage of RPKs they can replace. ICCT’s paper on hydrogen-powered aircraft presents the method for determining the replaceable market for such aircraft. This replaceable market is calculated as a preprocessing step and is dependent on the payload-range capability of the specified aircraft.

For example, let’s assume a liquid hydrogen (LH2) powered narrowbody aircraft can carry 165 passengers 3400 km. This payload-range capacity is compared to 2019 passenger aircraft operations data to determine the routes that are within the capability of the aircraft. The replaceable routes represent a fraction of the total RPK serviced by narrowbody aircraft in 2019. This fraction is enforced as the upper limit for the percentage of the narrowbody fleet that can be LH2-powered. We assume this fraction of replaceable routes stays the same through all the modelled years. If the maximum replaceable market of a particular aircraft, the sales share of that aircraft for the following years is reduced to be equal to the maximum replaceable market percentage.

3. Segment Activity

Since this model analyzes data on the operational segment level instead of specific aircraft level, we need to translate the fleet structure back into RPK space. The Segment Activity Module handles this process.

The model first sums up stock by aircraft class and merges the total stock count with the current-year RPK data based on aircraft class and propulsion. The model then calculates the RPK share of each unique combination of region pair and distance band within each aircraft class. The stock is broken down to each segment by multiplying the total stock count with the RPK share.

Once each segment is assigned the appropriate stock count, the stock is further broken down by propulsion. The model calculates the share of aircraft with each propulsion method within the segment and downscales the total RPK of that segment to each propulsion.

4. Energy

The Energy Module adds fuel efficiency information onto the segmented activity data. There are three types of efficiency variables: technical efficiency, payload efficiency, and traffic efficiency. These inputs are all unitless improvement factors, with model base year as the reference (factor = 1). For instance, when a future-year fleet has a 2% higher technical efficiency than the baseline, the efficiency factor would be 0.98. The efficiency factors are specific to each propulsion type and aircraft class.

For technical efficiency, factors before the base year are required to derive the fleet average efficiency. In the model, historical fuel efficiency factors come from ICCT’s fuel burn trends analysis; from 1970 to 2019, the average metric value of newly delivered aircraft each year improved by 1.1% annually. These historical factors are all greater than 1, since 2019 is the model base year. Future year efficiency factors, on the other hand, are all less than 1, and they come from user inputs. In each iteration, the modal takes in current year’s stock-by-age data, derives the delivery year by subtracting age from current year, and merges in technical efficiency factor based on delivery year. The function then calculates the stock-weighted average of technical efficiency factors by propulsion and aircraft class.

Because the reference (factor = 1) is new aircraft delivered in the base year, not the fleet-average technical efficiency in that year, the model normalizes current year’s technical efficiency to base year’s value.

Once we have the normalized average technical efficiency factors, we merge them with the baseline fuel efficiency (MJ/RPK) data (broken down by segment). The payload efficiency factors and traffic efficiency factors, both based on user inputs, are also merged. The traffic efficiency factors are multiplied by the user-specified formation flying scaler to reflect the further improvement in efficiency. Multiplying the baseline fuel efficiency (Y0) with all three of the efficiency factors of that year results in the modelled fuel efficiency of each segment in that year (Y1):

\[\frac{\text{MJ}}{\text{RK}P_{Y1}} = \frac{\text{MJ}}{\text{RP}K_{Y0}}*TechnicalEfficiency_{Y1}*PayloadEfficiency_{Y1}*TrafficEfficiency_{Y1}\]5. Fuels

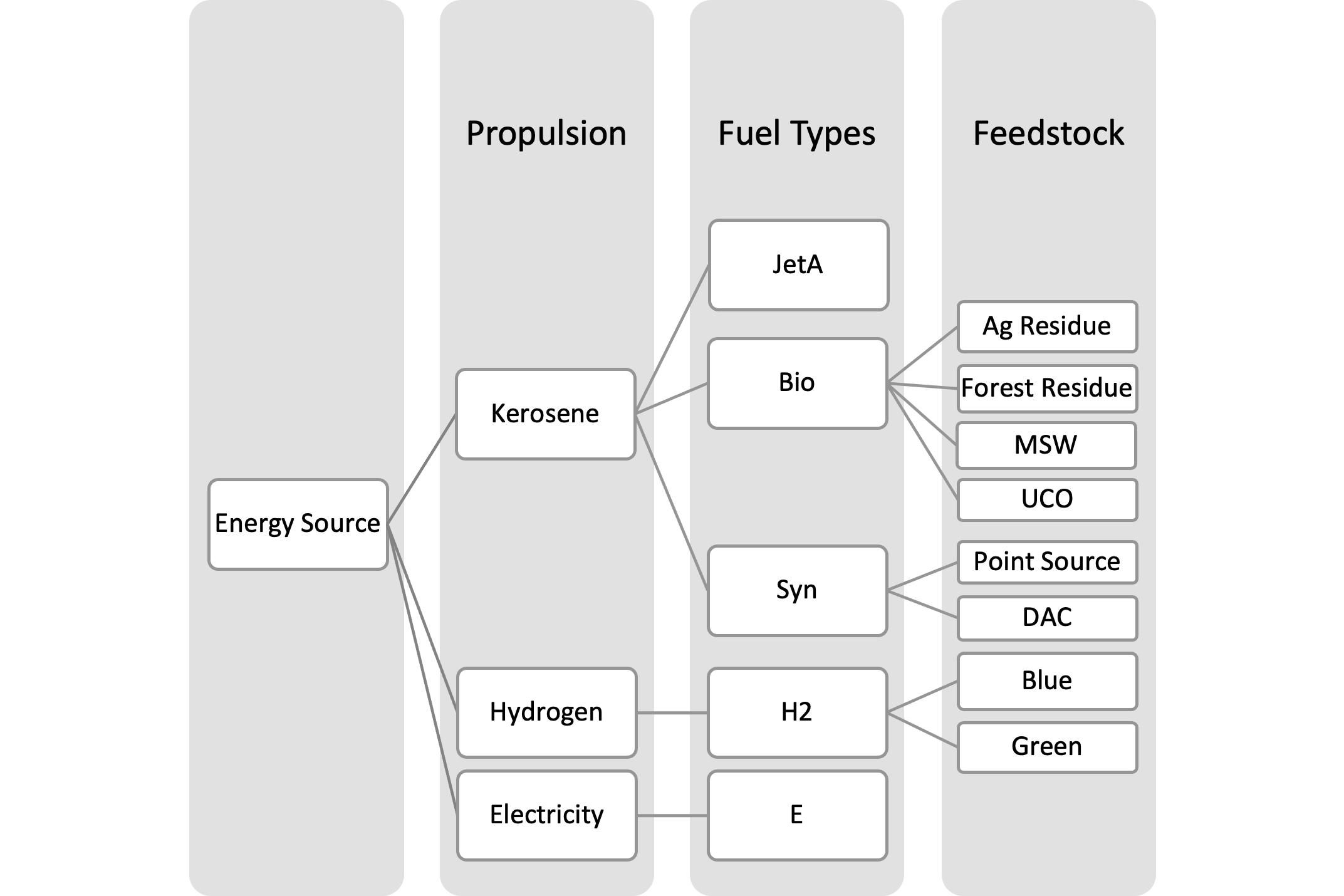

The Fuels module calculates the blend rate of SAF and the weighted average carbon intensity of each propulsion type. The carbon intensity inputs are on the feedstock level when different feedstocks are available for the same fuel type. The module processes the inputs to generate the carbon intensity of each fuel type and ultimately each propulsion type (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Propulsion methods and fuel types modelled. Fuel type names and feedstock names are specific variable names used in the model.

First, the model calculates the total energy demand for each segment (propulsion specific), for both passenger and freight operations:

\[MJ = RPK*\frac{\text{MJ}}{\text{RPK}} + FTK*\frac{\text{MJ}}{\text{FTK}}\]The module then processes the SAF blend share from user inputs based on the total kerosene demand and SAF volume inputs. When total kerosene demand is greater than total SAF supply, the gap is filled by conventional jet A. If total SAF supply exceeds total kerosene demand, the kerosene demand would be entirely fulfilled by SAF, based on the biofuel vs. synthetic fuel split in the supply. SAF blend shares always add up to 100%.

The model then calculates the weighted average carbon intensity of each fuel type (JetA, Bio, Syn, H2, and E) based on feedstock shares. Since hydrogen and electricity only have one fuel type respectively, their carbon intensity are simply those of “H2” and “E”. The carbon intensity of kerosene segments takes one extra step of averaging based on the volume split of conventional jet A vs. biofuel vs. synthetic fuel, based on calculations described above.

6. Emissions

This module simply performs the multiplication of energy demand and fuel emissions intensity to calculate the total CO2 emissions for each segment.

\[MJ*\frac{CO_{2}}{\text{MJ}} = CO_{2}\]7. Demand

The Demand Module translates the increase in fuel price to an increase in ticket price, and estimates demand response based on air travel’s demand elasticity to price. Fuel price in each year is estimated from baseline Jet A costs and SAF cost assumptions input by the user. Hydrogen and electricity, which are estimated to be lower cost fuels than SAFs for relevant segments, are not used to estimate demand response.

This analysis leverages the operations details from ICCT’s GACA model, which includes 82,694 route-aircraft type combos. Route-specific 2019 average economy-class airfare data were purchased from RDC; the data covers almost half of the 2019 passenger operations. For routes not covered by the dataset, we estimated their fare based on extrapolated “dollar per km” by stage length and by region. Demand elasticities are also matched to routes based on ICAO region pair and short vs. long haul. Pan-national level price elasticities are derived from InterVISTAS consultant report to IATA. The more detailed Boeing region pairs used in the model are matched to corresponding ICAO region pairs in advance.

Table 2. Air travel’s demand elasticities to price used in the model.

| Region Pair | Long-haul | Short-haul* |

|---|---|---|

| Africa-Africa | -0.36 | -0.4 |

| Africa-Asia/Pacific | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| Africa-Europe | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| Africa-Latin America/Caribbean | -0.72 | -0.79 |

| Africa-Middle East | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| Africa-North America | -0.72 | -0.79 |

| Asia/Pacific-Asia/Pacific | -0.57 | -0.63 |

| Asia/Pacific-Europe | -0.54 | -0.59 |

| Asia/Pacific-Latin America/Caribbean | -0.36 | -0.4 |

| Asia/Pacific-Middle East | -0.57 | -0.63 |

| Asia/Pacific-North America | -0.36 | -0.4 |

| Europe-Europe | -0.84 | -0.92 |

| Europe-Latin America/Caribbean | -0.72 | -0.79 |

| Europe-Middle East | -0.54 | -0.59 |

| Europe-North America | -0.72 | -0.79 |

| Latin America/Caribbean-Latin America/Caribbean | -0.75 | -0.83 |

| Latin America/Caribbean-Middle East | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| Latin America/Caribbean-North America | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| Middle East-Middle East | -0.57 | -0.63 |

| Middle East-North America | -0.6 | -0.66 |

| North America-North America | -0.6 | -0.66 |

*Short-haul flights are defined as less than 1,500km in great circle distance, and all other flights are categorized as “long-haul” for the purpose of matching elasticities.

In each analysis year, the module updates the total passenger count, fuel burn, and emissions for each route-aircraft type combo, based on the segment-level changes in traffic and energy consumption compared to previous year. The change in demand for each route-aircraft combo is then calculated based on the increase in ticket price, as below:

\[PriceInce = \frac{\text{FuelBurn}\left\lbrack L \right\rbrack}{\text{TotalPax}}*SafPriceDiff\left\lbrack \frac{\$}{L} \right\rbrack*PassThrough\] \[PctPriceInc = \frac{PriceInc + AvgFare}{\text{PriceInc}}\] \[NewPax = TotalPax*\left( 1 + Elasticity*PctPriceInc \right)\] \[NewRPK = NewPax*Distance\]The PassThrough variable refers to the percentage of increase in fuel costs that airlines typically pass on to consumers by increasing ticket prices. This pass-through rate is a user input.

The percentage of RPK change is summarized based on segment and passed on to the next iteration of the model, feeding into the Traffic Module. The updated fuel burn, emissions, and fare are also passed on for the next iteration of the Demand Module.

This module also calculates the implied carbon price from the fuel price increase. Near-term carbon prices were modeled as a fossil fuel levy and cross-subsidy to alternative fuels, while long-term carbon prices equal to the marginal cost of alternative fuels. Specifically, carbon prices are estimated in each year as the lesser of:

-

A cross-subsidy from fossil jet fuel to SAFs ($ of incremental SAF cost/tonnes of total aviation CO2)

-

A classic marginal abatement cost ($ of incremental SAF cost/tonnes of SAF CO2 abatement)

8. Freight

In addition to passenger travel and its emissions, the PACE model projects freight growth and its associated emissions. Freight carriage is split into two modes: belly freight carried on passenger aircraft, and dedicated freight carried on freighter aircraft. The freight market is measured in freight tonne kilometers (FTK) and the market is roughly equally split across belly and dedicated freight. Both belly and dedicated freight carriage are classified according to aircraft class and stage length. Thus, the varying efficiencies across aircraft class and stage length can be accounted for.

Input data for belly and dedicated FTKs for the first year is required. The belly FTKs are used to calculate the FTK-to-passenger revenue tonne kilometer (RTK) ratio where passenger RTK = RPK x 0.1 because each passenger is assumed to be 100 kg which is equal to 0.1 tonnes. Initial energy intensity for belly and dedicated freight is also required as an input in MJ/FTK.

Freight growth

A single global growth rate value is used to project freight growth. This growth rate is unaffected by carbon pricing. However, the split between belly and dedicated freight can change. The FTK/RTK ratio is kept constant, so belly freight FTKs grow according to growth in passenger traffic. The remaining freight is assigned to dedicated freight. A summary of the equations:

\[NewTotalFTK = OldTotalFTK*\left( 1 + FreightCAGR \right)\] \[NewBellyFTK = FTKPaxRTKRatio*\frac{\text{RPK}}{10}\] \[NewDedicatedFTK = NewTotalFTK - NewBellyFTK\]Freight emissions

The belly and dedicated FTKs are multiplied by the energy intensity to calculate the total MJ required for freight. Since belly freight is carried on passenger aircraft, the same efficiencies gained by passenger aircraft are applied to belly freight. Dedicated freighters tend to be older passenger aircraft that have been retired and converted to be dedicated freighters. While dedicated freighters can benefit from the same operational efficiency improvements as passenger aircraft, the technical efficiency improvements tend to lag those of passenger aircraft. For this reason, the annual technical efficiency improvement of dedicated freighters is an independent input and is generally kept lower than those for passenger aircraft.

The new energy efficiency of freight is calculated separately for belly and dedicated freight but follows the same formula.

\[NewMJperFTK = OriginalMJperFTK*TechEfficiencyImprov*PayloadEfficiencyImprove*EnRouteEfficencyImprov\]Here OriginalMJperFTK refers to the freight energy intensity in the base year. The EfficiencyImprov values are all relative to the base year efficiencies as well. As mentioned earlier, the module classifies freight carriage according to aircraft class and stage length. Each combination of these two variables has its own efficiency value.

We assume that no belly freight is carried on zero-emission aircraft and none of the dedicated freighters are zero-emission aircraft. Total emissions from freight then becomes:

\[FreightEmissions = \left( BellyFTK*MJperFTKBelly + DedicatedFTKDedicated \right)*CO_{2}\text{perMJKerosene}\]Scenario inputs

The PACE model can take in various user inputs for modeling customized scenarios. The table below shows the user/scenario inputs for ICCT’s Vision 2050 report.

Table 3. Model inputs that offer flexibility through user definition.

| Variables | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Efficiency | New aircraft fuel efficiency | -— |

| Payload Efficiency | Share of maximum structural payload carried by airlines; proxy for load factor and one input into operational efficiency | -— |

| Traffic Efficiency | Relative airport and air traffic management efficiency; one input into operational efficiency. | -— |

| Formation Flying | Formation flying scaler for traffic efficiency | -— |

| Fleetwide Efficiency | Product of base year efficiency and technical, payload, and traffic efficiency | MJ/RPK |

| ZEP Sales Share | Sales share of zero-emission planes | % |

| SAF Volume | Available SAF volume | EJ |

| SAF Cost | SAF price | $/L |

| Feedstock Share | Share within a fuel type based on volume | % |

| Pass Through | Fuel cost increase passed on to consumers | % |

| Modal Shift | RPK shifted to rail by segment | % |

| Freight Technical Efficiency | Annual fuel efficiency improvements of dedicated freighters | -— |

Future work

We are planning to extend the model’s capability for conducting country-level analyses. Our base year data have country details, so the model could either downscale results to countries or take in country-specific inputs to make projections.

The model can also add functionality to model varying utilization rates of aircraft at different ages (by incorporating utilization curves) as well as potential aircraft scrappage policies.

The model may eventually include estimates for non-CO2 emissions from aviation.

Glossary

Bio: biofuel, fuel derived from biomass

CAGR: compound annual growth rate

CO2: Carbon dioxide

CY: Current year

DAC: direct air capture

DY: Delivery year

EJ: exajoule

FTK: freight tonne kilometers

GACA: Global Aviation Carbon Assessment model (ICCT’s aviation CO2 inventory)

IATA: International Air Transport Association

ICAO: International Civil Aviation Organization

ICCT: International Council on Clean Transportation

LH2: Liquid hydrogen

MJ: megajoule

MSW: municipal solid waste, as a source of aviation fuel

p.a.: per annum

PACE: Projection of Aviation Carbon EmissionsRPK: revenue passenger kilometers (RPKs), a measure of airline passenger traffic by multiplying the number of fare-paying passengers on each flight by the flight distance.

RTK: Revenue tonne kilometers

SAF: sustainable aviation fuel

Syn: synthetic fuel, or power-to-liquids fuel

UCO: used cooking oil as a source of aviation fuel

ZEP: zero-emission planes, either hydrogen or electricity powered.