EV CHARGE v1.0 Documentation

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Scope of the model

- Methodology

- Inputs and outputs of the model

Introduction

A crucial factor in achieving our climate goals and promoting the adoption of zero-emission vehicles is the identification and implementation of appropriate charging infrastructure at the right pace and location. Recognizing the complexity of this task, the ICCT has developed EV CHARGE, a Python-based model designed to evaluate the charging infrastructure requirements for light-duty vehicles (2 and 3 wheelers, passenger cars, and light commercial vehicles) across various scales, from local (e.g., city district level) to supra-national (e.g., European Union level), and for any market and time horizon, using a specified set of inputs. It’s important to note that this model is exclusively for internal use and is intended to streamline and standardize the assessment of charging needs.

The EV CHARGE (Electric Vehicle CHArging and Refueling GEnerator) model serves as a valuable tool for governments and various stakeholders, including NGOs, private sector charge point operators, businesses, and others, offering a comprehensive understanding of the electric vehicle ecosystem. With its ability to determine the required number of chargers by type and the installed power output per EV, the model aids in setting precise goals and informing policy-making decisions. Moreover, this model empowers policy makers to monitor and ensure that their jurisdiction is progressing towards achieving their electrification objectives.

The development of this model was funded through the generous support of the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, the European Climate Foundation, Climate Imperative, and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Scope of the model

The Python-based EV CHARGE model offers a versatile solution for evaluating the EV charging infrastructure requirements of any jurisdiction, encompassing various light-duty vehicle types and segments. The supported vehicle types include 2-3 wheelers, passenger cars, and light commercial vehicles. Moreover, the model allows for a flexible sub-division of these vehicle types into segments, accommodating distinctions such as private vs. company cars, with the potential for further divisions based on company names or business types, as well as considerations for taxis, ride-hailing vehicles, and more. This adaptability ensures a comprehensive analysis tailored to the specific needs and characteristics of each jurisdiction and user.

The EV CHARGE model accommodates jurisdictions ranging from entire markets like the European Union to smaller city districts like Charlottenburg, Berlin, Germany. While it theoretically operates at any level based on user-provided data, reliable information below the city district level is uncommon. Instead of offering precise charger locations (latitude and longitude), the model provides the total number of chargers for specific types (e.g., public destination AC, 11kW) within a given jurisdiction (e.g., city district) and year. Subsequently, users can collaborate with municipalities to identify potential charger locations, considering factors such as land availability, grid constraints, and other relevant considerations.

The charger needs assessed in the model fall into two primary categories: private and public. Each category is then divided by location, including home, depot, workplace, public overnight, public destination, and en-route (highway). Optionally, further sub-locations can be considered, such as destination chargers dedicated to taxis. The charger types are categorized as Level 1, Level 2, and DC fast. Additionally, within a charger type, chargers can be further specified by capacity, such as 3.7 kW, 7.4 kW, 11 kW, and 22 kW. This comprehensive breakdown allows for a detailed assessment of charger requirements across various scenarios and use cases.

Methodology

The model employs two distinct methodologies: an energy-based approach and a minimum coverage approach. Each methodology is better suited for specific charger types and locations, as illustrated in the Table below. For certain charger types, the number required is influenced less by the annual energy delivery and more by achieving minimum coverage concerning factors like the maximum distance between stations, the number of vehicles, or the population.

To apply each methodology effectively, different sets of inputs are required. These inputs encompass comprehensive fleet composition information that covers the entire analysis scope, including all vehicle types, regions, and relevant analysis years. Additionally, regional insights into the behavior of EV owners and technical details about chargers are necessary to facilitate accurate assessments. The combined use of these methodologies and inputs enables a comprehensive and tailored analysis of charger needs in diverse scenarios.

Table 1: EV CHARGE methodologies and the locations for which they can be used for the analysis.

| Charger's location | Energy-based methodology | Minimum coverage methodology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on the number of vehicles | Distance-based | Population-based | |||

| Private | Home | No | Yes - Default | No | No |

| Depot | Yes - Optional | Yes - Default | No | No | |

| Workplace | Yes - Default | No | No | No | |

| Public | Overnight | Yes - Default | No | No | Yes - Optional |

| Destination | Yes - Default | No | No | Yes - Optional | |

| En-route | Yes - Optional | Yes - Optional | Yes - Default | No | |

Energy-based

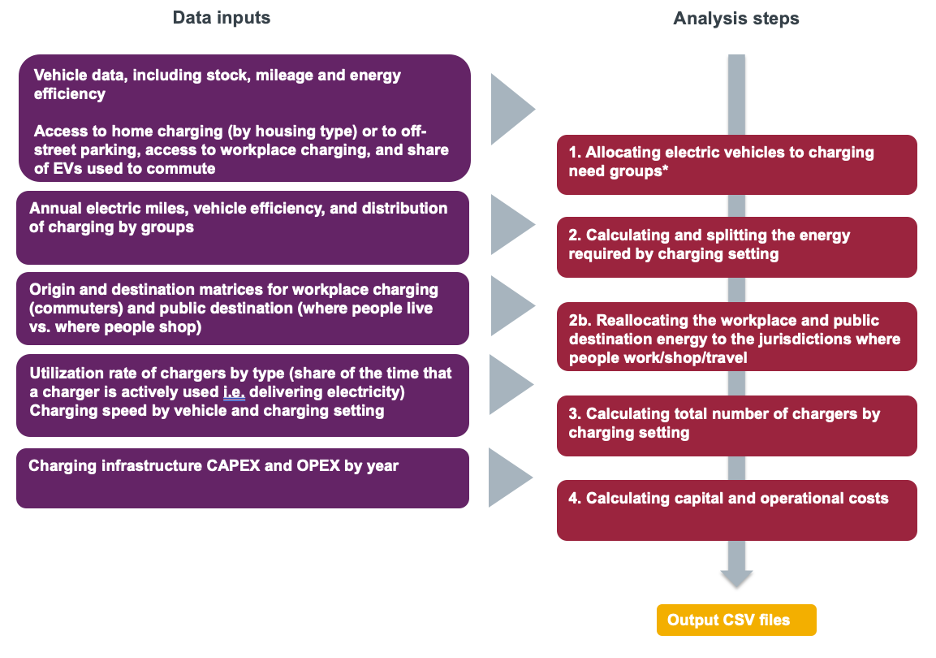

Figure 1 depicts the energy-based methodology that is particularly well-suited for assessing public overnight and destination charging, as well as private workplace charging. The purple rectangles in the figure signify the data inputs required for each step, which are then represented by the red rectangles. This methodology is applied for every year and jurisdiction within the analysis. By following this approach, accurate evaluations of charging needs for various scenarios can be obtained, specifically focusing on the mentioned charger types in different locations.

Figure 1. Energy-based charging infrastructure modeling for light-duty vehicles. ( *Charging need group = regrouping vehicles with the same characteristics and charging patterns. For example, a group could be composed of long-range BEVs used to commute to work and with access to home and workplace charging.)

The following sections will provide information on each analysis step.

Allocating electric vehicles to charging needs groups

The EV stock is allocated to specific EV owner groups for each year of the analysis. These groups are formed based on similar charging behaviors exhibited by EV owners.

For passenger cars, a minimum classification involves dividing EVs into groups based on the following criteria: vehicle powertrain (BEV vs. PHEV), availability of home charging, commuting status (car commuter vs. non-car commuter), and availability of workplace charging.

For light commercial vehicles (LCVs), the minimum classification entails splitting EVs into groups based on vehicle powertrain (BEV vs. PHEV), location of overnight parking (depot vs. home), and home charging availability for LCVs without access to a depot.

Regarding 2 and 3 wheelers, the minimum group characteristics include powertrain, home charging availability, depot charging availability, commuting status, and workplace charging access for commuters.

The decision to establish this minimum classification is supported by EV drivers’ surveys and market research. These studies have revealed that EV drivers’ charging behavior is significantly influenced by the accessibility of home, depot, and workplace charging options.

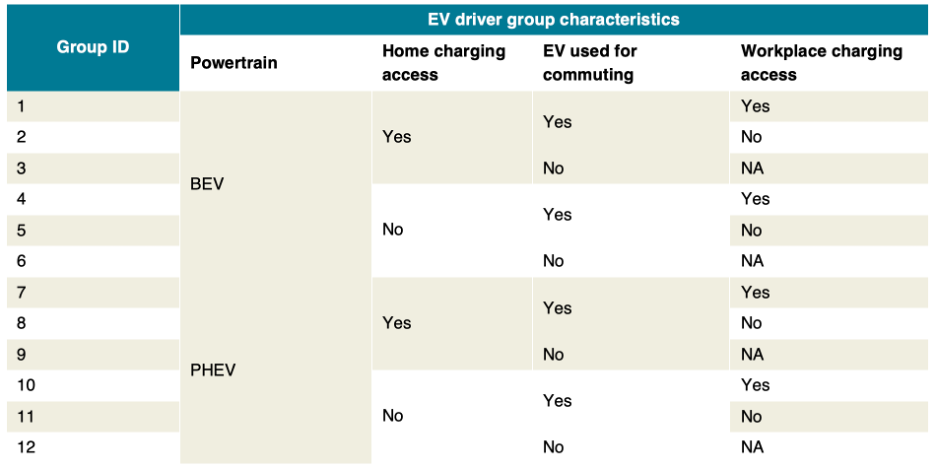

Table 2 below provides an example illustrating the basic user groups for passenger cars. This systematic classification enables a more comprehensive analysis and understanding of EV charging behaviors in various contexts.

Table 2: Example of basic EV groups for private passenger cars

The model is designed to accommodate additional user group differentiations based on available data and market characteristics. This flexibility is facilitated by a variable called “Consumer type.” Users can define various consumer types to represent different segments of EV owners, considering factors such as income, vehicle range, and vehicle type.

For instance, consumer types could include categories like “high-income and long-range vehicle,” “low-income and long-range vehicle,” “high-income and short-range vehicle,” and “low-income and short-range vehicle.” Moreover, for light commercial vehicles (LCVs), behavior groups can be based on specific use types, such as delivery vehicles or trade vehicles for various professions like plumbers, carpenters, and other craftsmen.

Splitting EVs into these distinct behavior groups requires significant data, which may not always be readily available. To overcome this challenge, the model often relies on proxy indicators. For instance, household dwelling type serves as a proxy for home charging availability. EV owners residing in houses are more likely to have access to home charging compared to those living in apartments. Similarly, whether EV owners own or rent their homes can be used as a proxy for the likelihood of having access to home charging.

By using these proxies and adapting to available data, the model can still provide valuable insights into the charging behavior of different user groups, even in situations where comprehensive data may be limited.

Calculating and splitting the energy required by charging setting

In Step 2 of the model, the daily energy required for each charging group is forecasted, considering factors like annual electric mileage and vehicle efficiency (measured in kWh per mile). Vehicle efficiency accounts for technological advancements and changes in vehicle mass over time. This calculation results in an estimation of the annual electricity demand (in kWh) for each group.

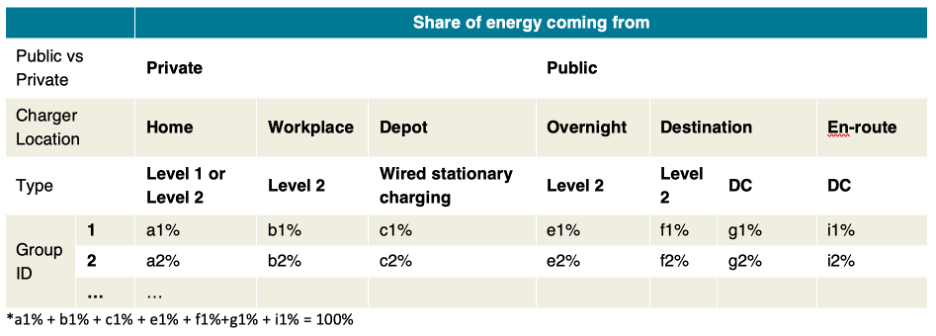

Next, this total energy demand is distributed among different charging settings, as defined earlier (based on the location and type of charger). Table 3 below presents an example of how the energy demand is allocated among various charging settings.

The distribution of energy demand across charging settings is influenced by insights obtained from charging behavior surveys of EV drivers and relevant regulations. For instance, if a jurisdiction offers incentives favoring workplace charging or provides free public destination AC charging, the share of energy drawn from these two settings may increase accordingly. These factors help fine-tune the allocation of energy demand, ensuring a more accurate representation of real-world charging patterns within different charging environments.

Table 3: Example of energy split by charging setting.

Reallocating energy demand

In the case of home and public overnight AC chargers, the chargers are typically located where people live, which aligns with their vehicle registration locations. However, this is not the case for workplace, public destination, and en-route chargers. For public destination chargers, they are usually situated in areas where people shop, use public transit, or engage in leisure activities. Similarly, workplace chargers are located at places of employment, not necessarily where people reside.

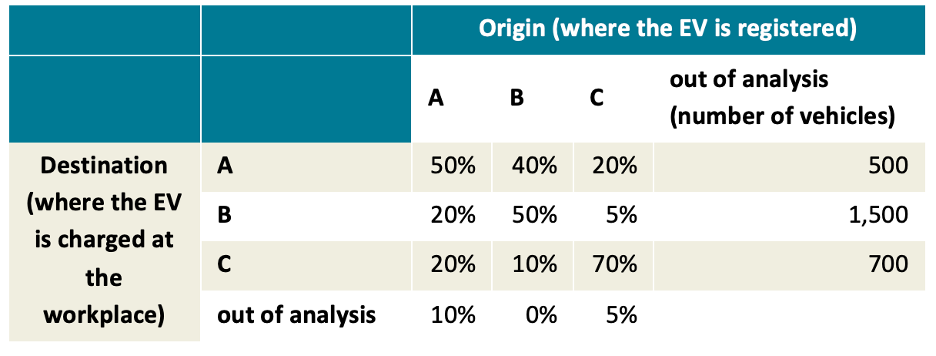

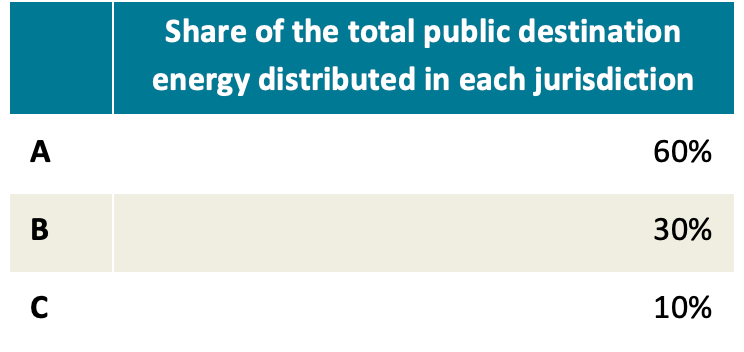

To address this distinction, the user is required to input origin-destination matrices to properly reallocate workplace and public destination charging needs to the correct locations. While commuting origin-destination data is usually available, obtaining origin-destination data for public destination charging locations can be more challenging. As a result, the model often aggregates all the energy delivered through this type of charging at the analysis level and then distributes it among jurisdictions based on relevant proxies.

For example, proxies used for public destination charging location can be derived from information such as the square footage of commercial centers or the number of parking spaces available in each jurisdiction. This helps to approximate the appropriate distribution of energy demand for public destination charging across different locations.

To illustrate, if an analysis consists of three jurisdictions (A, B, and C), the origin-destination matrix for workplace charging could be represented in Table 4, while the reallocation of public destination energy demand could be demonstrated in Table 5. The last row and column in Table 5 pertain to scenarios where some vehicles needing to charge fall within the jurisdictions being analyzed but come from outside of that analysis. In such cases, the user is required to provide an additional input file for “out of analysis vehicles.” This comprehensive approach allows for a more accurate representation of charging behavior and energy demand patterns within the analyzed regions.

Table 4: Origin-Destination matrix example for workplace energy demand

Table 5: Redistribution of energy demand for public destination charging

Calculating the total number of chargers needed

Step 3 converts electricity demand (kWh) into the required number of chargers, considering charging efficiency, active utilization, and speed.

Charger and on-board converter efficiencies

The model considers two types of energy losses during EV charging, which vary based on the charging type (e.g., AC or DC). The first is the charger efficiency (electricity exiting the charger)/(electricity entering the charger), representing the ratio of electricity exiting the charger to electricity entering it. The second is the vehicle on-board efficiency (electricity entering the battery of the EV)/(electricity exiting the charger), reflecting the ratio of electricity entering the EV’s battery to electricity exiting the charger. These losses primarily occur due to AC-DC conversion during the charging process.

Charger active utilization

For public and workplace chargers, the model employs a logarithmic increase in active utilization, which refers to the time when power is actively drawn from the charger, excluding plugging and payment downtimes. This increase in utilization is linked to the electric vehicle stock share and continues until it reaches a maximum utilization rate at mass EV adoption. Equation 1 represents the calculation used for this purpose.

The coefficients ‘a’ and ‘b’ in the equation are determined based on assumptions for minimum and maximum utilization levels associated with specific EV stock shares. The model ensures utilization remains constant before reaching the minimum stock share and after reaching the maximum stock share. For instance, the default maximum utilization rate is set at 6 hours per day for public wired stationary chargers (equivalent to 25% utilization). However, users have the flexibility to adjust these values according to their specific needs and preferences.

\[\text{Active charger utilization (in percentage of the time)} = a \cdot \ln(\text{EV stock share}) + b\]Charging speed

For each year of the analysis, the model estimates the average power delivered by each charger type (e.g., AC overnight, AC and DC destination, and DC en-route) and capacity (e.g., 22kW and 50kW). It’s important to note that the average power actively delivered during a charging session should not be confused with the rated power output of the charger, as the former is often limited by the vehicle’s capabilities.

For example, even though a 50kW charger is rated to deliver 50kW, it might only provide an average of 45kW during a charging session. This average power delivery primarily depends on factors like the vehicle’s charging acceptance rate, the start and end state of charge (SOC) of the vehicle, and the rated power output of the charger.

As a default assumption, the model considers a gradual increase in the power delivery ratio (average power delivered during a session)/(rated power output of the charger) over the years. This is attributed to technological advancements and a better understanding of vehicle capabilities by EV drivers. For instance, in the early years, some BEV drivers might attempt to use 100kW DC chargers even if their vehicle can only accept 50kW. However, as understanding improves over time, such scenarios are less likely to occur in later years. Similarly, the likelihood of BEV drivers attempting to charge their vehicle at a DC fast charger above 80% SOC decreases as time progresses.

These default assumptions help account for the evolving nature of EV charging behavior and technological developments, leading to more efficient and optimized charging practices over time. The user can overwrite the default assumptions with their own yearly power delivery ratio values.

Calculation summary

Based on the information provided in Table 3, which indicates the percentage of energy to be delivered through a specific charger type for a particular user group, the model calculates the number of chargers required for a given jurisdiction and year using the equation below. This equation is simplified for one behavior group, and the model the needs of all user groups that depend on the specific charger type under consideration.

\[\begin{align*} & \text{Number of chargers of a certain location, type and capacity} = \\ & \hspace{2em} \text{#vehicles in the user group} \cdot \frac{miles}{day} \cdot \text{vehicle efficiency (kWh/mile)} \\ & \hspace{2em} \cdot \text{x % : share of energy coming from this charger category for the consumer group} \\ & \hspace{2em} \cdot \frac{1}{\text{power delivery ratio} \cdot \text{rated power output}} \cdot \frac{1}{\text{utilization share} \cdot 24 \text{hrs}} \end{align*}\]Minimum coverage

There are three sub-types of minimum coverage methodologies: vehicle-based, distance-based, and population-based.

Vehicle-based

This methodology primarily applies to private home and depot chargers.

For private home chargers, the total number of chargers correlates directly with the electric vehicle stock. By default, one home charger per Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV) with access to home charging is assumed, and slightly less than one charger per Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) with access to home charging, considering that PHEVs may share chargers with other electric vehicles. In apartments, the default is one home charger per two electric vehicles. However, users have the flexibility to modify these default values to suit their specific requirements.

Regarding depot chargers, the user is prompted to provide a ratio of installed power output in kilowatts (kW) per BEV and per PHEV. By default, the model assumes 8kW of installed power output per BEV and 4kW per PHEV. Additionally, the user can specify the type of chargers utilized by the fleet of vehicles using these depot chargers. For example, the fleet could source half of their energy from 11kW AC chargers and the other half from 50kW DC chargers at the depot.

While this methodology is not the default approach for calculating the number of en-route chargers, it is possible to use it for this purpose. In this alternative approach, the number of en-route chargers could depend on the number of BEVs on the road, rather than being solely determined by the distance between two charging stations or the energy they need to provide. This flexibility allows users to tailor the model to different scenarios, ensuring accurate assessments based on their specific needs and preferences.

Distance-based

This methodology is primarily utilized for fast chargers along road corridors, specifically for public DC en-route charging.

The number of DC en-route chargers is determined based on the length of the road network and specific requirements regarding the maximum distance between charging stations and the minimum number of chargers per station. Unlike other charger types, the number of corridor chargers needed is less dependent on the annual energy they need to deliver and more focused on establishing a basic coverage capable of meeting the vehicle throughput on high-activity days, such as holidays and weekends.

For example, if a road network in the jurisdiction spans 1,000 km, and regulations stipulate the need for charging stations every 100 km with a minimum of 4 chargers per station, then the jurisdiction will require 40 public en-route chargers spread across 10 different stations.

It is the user’s responsibility to provide the roadway length per jurisdiction along with the number of charging stations required every 100 km, enabling the model to accurately assess the number of public en-route chargers needed to meet the charging demands of electric vehicles traveling along the road corridors within the jurisdiction.

Population-based

In certain jurisdictions, a minimum number of chargers may be required based on the population to achieve equitable charging access and provide basic coverage. Once this minimum requirement is fulfilled, additional chargers can be strategically deployed where demand exists, utilizing the energy-based approach. This straightforward methodology effectively ensures minimum equitable coverage for public overnight and destination charging facilities.

Calculating investments needed

In an additional step (Figure 1, calculation step 4b.), the total cost of both public and private charging infrastructure is estimated by considering charging infrastructure capital and operational costs. Capital costs typically encompass categories such as hardware, software, planning, installation, grid connection, grid upgrades, and land acquisition. Operational costs usually include maintenance, grid upgrades, and land rental. The allocation of grid upgrades and land costs may appear in both operational and upfront costs, depending on specific business arrangements. For instance, utilities might offer charge point owners the option to spread grid upgrade costs over multiple years, and charge point operators could either purchase or rent the land.

Moreover, users can input additional capital and operational cost categories as needed. For example, the cost of permits could be included if relevant to the charging infrastructure project. By estimating the total cost of charging infrastructure, this step enables a comprehensive assessment of the financial implications involved in establishing and maintaining both public and private charging facilities.

Inputs and outputs of the model

Inputs fed to the model

The inputs required to run the model are categorized into Default, User-provided mandatory, and User-provided optional.

Default inputs are automatically provided when using the model but can be modified by the user to better suit the analyzed market. User-provided mandatory inputs are essential and must be supplied to run the model successfully. Without them, the model cannot be executed. Lastly, user-provided optional inputs can enhance the accuracy of the results if available for the specific market analysis, although they are not obligatory.

Table 6 lists all the input files classified into these three categories. Inputs marked with an asterisk (*) signify non-mandatory files that can significantly improve result precision when provided by the user to adapt to the market’s specificities. All inputs can vary based on vehicle type (PC, LCV, 2-wheeler, 3-wheeler), segment (e.g., taxi, company car, vehicle operated by company A), and jurisdiction. Some inputs are constant throughout the analysis, while others may change depending on the year or the EV stock share, as indicated in italics after the input name: f(years) or f(EV stock share).

Table 6: Inputs fed to the EV CHARGE model.

| Default | User-provided mandatory | User-provided optional |

|---|---|---|

EV per charger (e.g., EV per home charger in apartments and per home charger in houses), f(EV stock share) |

EV fleet input data (sales or stock, VKT, efficiency), f(year) |

Consumer type |

kW per EV depot charger (mostly for LCVs and taxis), f(EV stock share) |

Housing share of EV owners, f(EV stock share) |

*Charger density by distance, f(year) |

Depot charging type, f(EV stock share) |

Share of EVs used to commute, f(EV stock share) |

*Roadway length |

*Home charging access share for various dwelling types, f(EV stock share) |

Depot charging access (mostly for LCVs and taxis), f(EV stock share) |

Charger density by population, f(year) |

*Share of workplaces offering charging access, f(EV stock share) |

Population | |

| *Commuter VKT ratio (ratio of VKT driven by commuters vs non-commuters) | Charger lifetime by installation year, f(year) |

|

*Charger upfront cost, f(year) |

*Current charger installed base | |

*Charger operating cost, f(year) |

Age distribution of existing chargers | |

Efficiencies (charger and on-board efficiencies), f(year) |

*Redistribution of workplace chargers | |

*Charger power delivery ratio (average power delivered during a session vs. rated power output for each charging setting), f(year) |

*Redistribution of public destination chargers | |

Charger utilization, f(EV stock share) |

Redistribution of depot chargers | |

Evolution of new charger installed share per rated power output, f(year) |

Out-of-model vehicles, f(year) |

|

| Min SOC | ||

| *User group definition (see Table 2 for an example) | ||

| User group usage share (see Table 3 for an example) |

Outputs of the model

After entering the required inputs into EVCHARGE, selecting the desired methodology for each charging setting, and executing the model, the user will obtain three CSV files as outputs.

The first CSV file will include the total number of chargers for each charging setting, jurisdiction, and year of the analysis.

The second CSV file will provide a detailed breakdown of the cost per charger type (e.g., grid connection, land, hardware, software) for each charger setting.

Finally, the third CSV file will list the yearly energy grid demand, reflecting the energy needs of the fleet and accounting for energy losses due to charger inefficiencies. The energy data will be organized by charger setting, jurisdiction, and year.